Remember Dolly the sheep?

It’s the first thing I think of any time I hear the word “clone.” It took scientists many years, but eventually they were able to create the world's first mammal cloned from an adult somatic cell.

Luckily, cloning mushrooms isn’t nearly that complicated.

In fact, it’s something any budding mycologist can easily do at home.

Why Clone Mushrooms?

✓ Capture Wild Strains

Cloning wild fruits allows you to copy mushrooms from the wild and cultivate them.

✓ Finding Valuable Traits

Cloning allows you to copy fruits that have interesting genetic variations, color, shape, etc.

✓ Clone Cultivated Mushrooms

You can also copy store bought mushrooms, or mushrooms that you have cultivated yourself.

There are several reasons why you’d want to clone mushrooms.

First of all, the forest is the original source for all commercial mushroom strains. Now, you could try to collect spores to propagate these wild mushrooms- but it would be a gamble, not knowing what type of genetics you’d end up with.

Cloning, on the other hand, allows us to take new mushroom strains from the wild, easily make identical genetic copies in the lab, and eventually cultivate them for food or medicine. With cloning, you have a better chance of getting a prolific strain. If growing outside, it will already be genetically adapted to your local environment.

Cloning also allows us to copy mushrooms with interesting characteristics and unique genetics- such as larger fruits, faster colonization times, or a whole array of other potentially valuable traits- and capture those traits for future benefit.

The Cloning Process

The process of cloning mushrooms is relatively simple, and basically the same whether cloning wild species, cultivated species, or even store-bought fruits.

All you need to do is harvest a piece of tissue from a mushroom fruitbody, place it on agar, and allow the mycelium to grow out until you have pure culture.

Easy!

This strategy works because the mushroom fruitbody, even after being picked, is still a living, breathing, manifestation of mycelium.

The cells are still willing and able to reproduce.

By transferring the live tissue to a nutrient rich agar media, the cells can spring into action, propagating mycelium across the plate.

Why Not Start From Spores?

You could always search for novel strains by starting from spores, instead of creating a clone. The problem is that spores are a total crapshoot. When you dump millions of spores on an agar plate, they will germinate and start to grow “hyphae”, single celled filaments which contain exactly half the genetic information required to form a fruitbody. To form mycelium, two hyphae need to meet. When they do, they essentially create a new strain- with any number of potential genetic variations. The results are very unpredictable, which is why commercial growers start from copies of proven strains, rather than spores. Cloning is a way to guarantee that the genetics of your culture will be the same as the genetics of the fruit which the clone was taken from. That being said, starting from spores does have it’s applications, just not if you are looking for predictable results.Harvesting Tissue

The tissue can be taken from any part of the mushroom fruitbody, but some of the best sites to harvest reproductive cells are the stem butt (which often contains remnants of mycelium), close to the gills underneath the cap, or smack dab in the middle of the stem. NOTE: It is not recommended to harvest actual gill tissue, mainly because it will be difficult to ensure cleanliness, and because it will be covered in mushroom spores- which may germinate and create a novel strain different from your clone. It is also hard to ensure cleanliness if taking tissue from the stem butt, since it has been exposed to contaminate rich environments. If possible, I like to take tissue from the inside of the stem, because that is where you get the cleanest sample- even though it may be a little slower to grow than the rapidly reproducing cells directly under the gills.

Cloning At Home

You can easily perform clones at home... so don't be afraid to give it a shot.Step 1: Select Fruit and Clean

First thing you want to do is select the fruit. Try and find a relatively large fruit body, since extremely small specimens, or thin fleshed species can be hard to obtain clean tissue samples from. You’ll then want to clean the outside of the fruitbody by thoroughly wiping it down with an alcohol soaked cloth. This will damage the mushroom and make it not suitable for eating, so you’ll need to be willing to sacrifice it for the clone. The reason we do this is because the outside of the fruitbody has been exposed to air and is no doubt covered in all sorts of contaminates- which could easily find their way onto the plate. Wiping the fruit down won’t completely eliminate the hazard, but it will significantly reduce the potential for contamination.

Step 2: Tear Fruit In Half

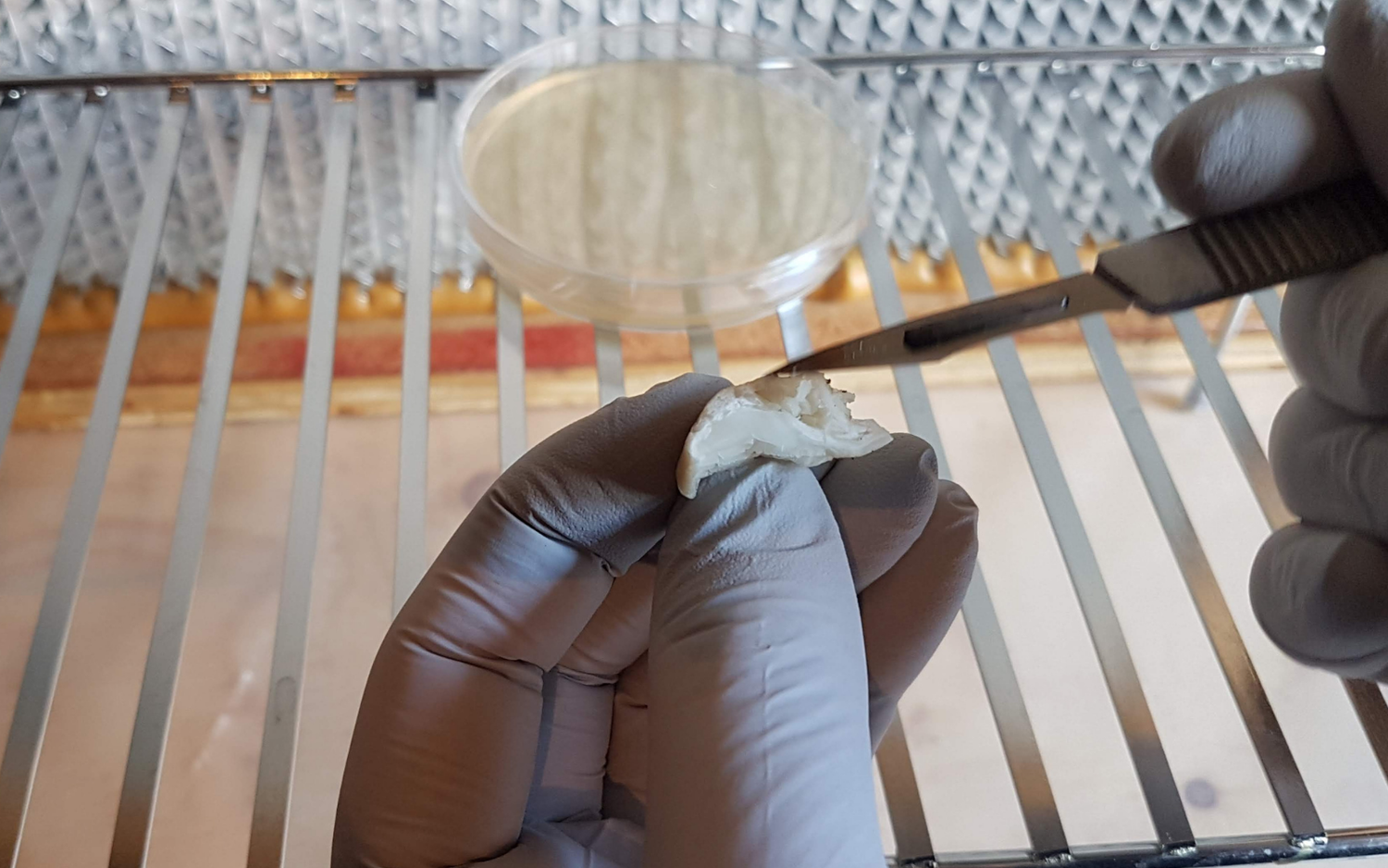

Once the fruitbody has been cleaned, tear it in half in a sterile environment. In front of a flow hood is best, but this can also be down in a SAB (still air box). You should tear the fruit rather than cut it to prevent pushing contaminates from the outside of the fruit into the center of the fruitbody. The inside of the mushroom will be naturally sterile and contain nothing but fertile mushroom cells. If using a flow hood, remember to always keep the fruitbody downstream of the flow hood.

Step 3: Transfer Tissue

Take a flame sterilized scalpel and remove a small piece of tissue from inside of the fruit body. I usually like to flame sterilize the scalpel before tearing the fruitbody in half, allowing it to cool in the stream of the flow. You can also force it to cool by dipping it in the clean agar plate before transfer. Either way, the scalpel should be cool before contacting the mushroom, otherwise it will likely kill the tissue. There are many places to remove tissue- but the easiest to work with is the thickest, fleshiest part of the mushroom. This is typically the center of the stem or the center of the cap, and will vary depending on species. Just keep in mind that basically anywhere you take the tissue will contain cells that are suitable for cloning. Remove the tissue by scraping your scalpel along the fruit a few times. You can also cut a small 1/8” square, but this is usually more cumbersome. Bring the tissue upstream and place it on the agar dish. This motion should be smooth and quick as possible, minimizing the time that the agar plate is open. This is especially true if using a SAB. I like to put at least three pieces of tissue in a triangle pattern on one single plate. Not every tissue will take off, and some will be contaminated, so placing multiple pieces of tissue on each plate will be more economical.

Step 4: Clean, Colonize, and Store

Once the plates have been inoculated and wrapped in parafilm or masking tape, store them on a shelf at room temperature away from direct sunlight. I like to also place the plates in a Ziploc bag to keep them free from dust or other airborne contaminants. Watch the plates closely, and over the next 2-3 days you should see mycelium starting to grow radially from the tissue. It is possible to get a clean culture on the first shot, but there is also a good chance that your plate will contain contamination, especially if working with wild clones. If that is the case, simply perform culture transfers by removing a piece of clean mycelium from the contaminated plate onto a new dish. Repeating this process a few times should eventually give you a clean culture to work with. Of course, if your plate is overly contaminated, and there is no visible clean mycelium, it may be best to throw it out and try again.

Cloning Examples

Wild Mushrooms

This is one of the best use cases for cloning mushrooms. One of my favorite things to do is find interesting mushrooms out in the forest, bring them back in the lab, and try to save the culture through a clone. This is a species of Trametes (Trametes hirsuta) that I cloned recently, which only took one transfer to get a clean culture. Not sure if this is something worth cultivating, but it is still fun to have a culture saved in perpetuity.

I also recently cloned an Agaricus species (Agaricus campestris), which should be a fun challenge to try and cultivate at home.

Of course, when cloning wild mushrooms for the purposes of cultivation and consumption, you’ll want to be absolutely 100% sure you have a positive ID of the species.

Store Bought Mushrooms

Another interesting use case for cloning is to make copies of store bought mushrooms. You can clone store bought Shiitake, Button Mushrooms and even Oysters. When doing this, try to get your specimens as fresh as possible to increase your chances of success. Here is a Shiitake that was cloned from a store-bought mushroom.